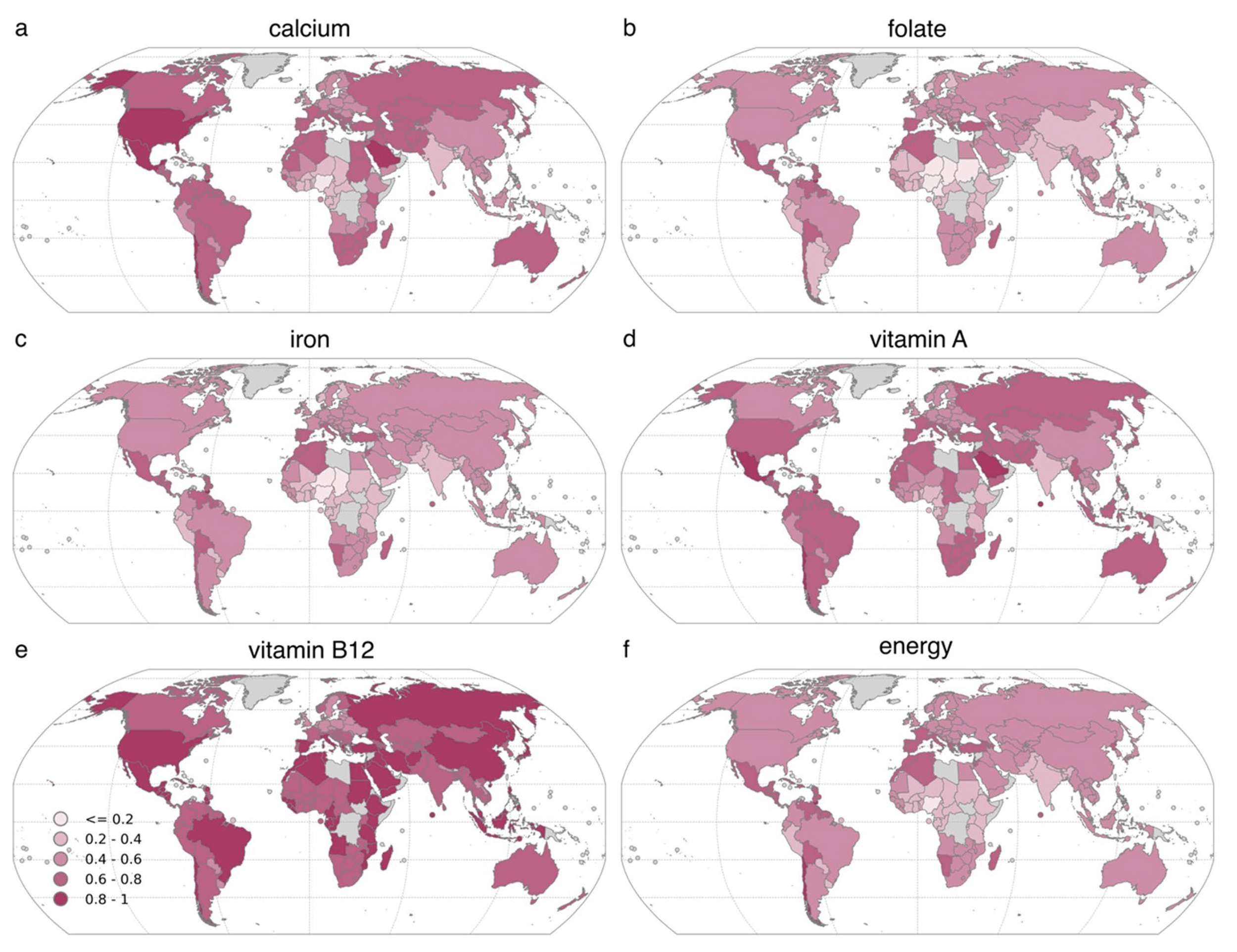

In 2025, we published a paper titled "Nutrition-Sensitive Climate Risks Across Food Production Systems" led by Michelle Tigchelaar. It presents an important analysis linking food security, micronutrient deficiency, and climate change. The objective of the paper was to assess nutrition-related climate risks across various food production systems. This is critical as both malnutrition and climate change pose significant threats to public health and food security, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where deficiencies are prevalent. We focused on five key micronutrients: calcium, folate, iron, vitamin A, and vitamin B12, selected for their vital roles in human health and the high rates of deficiencies associated with their lack.

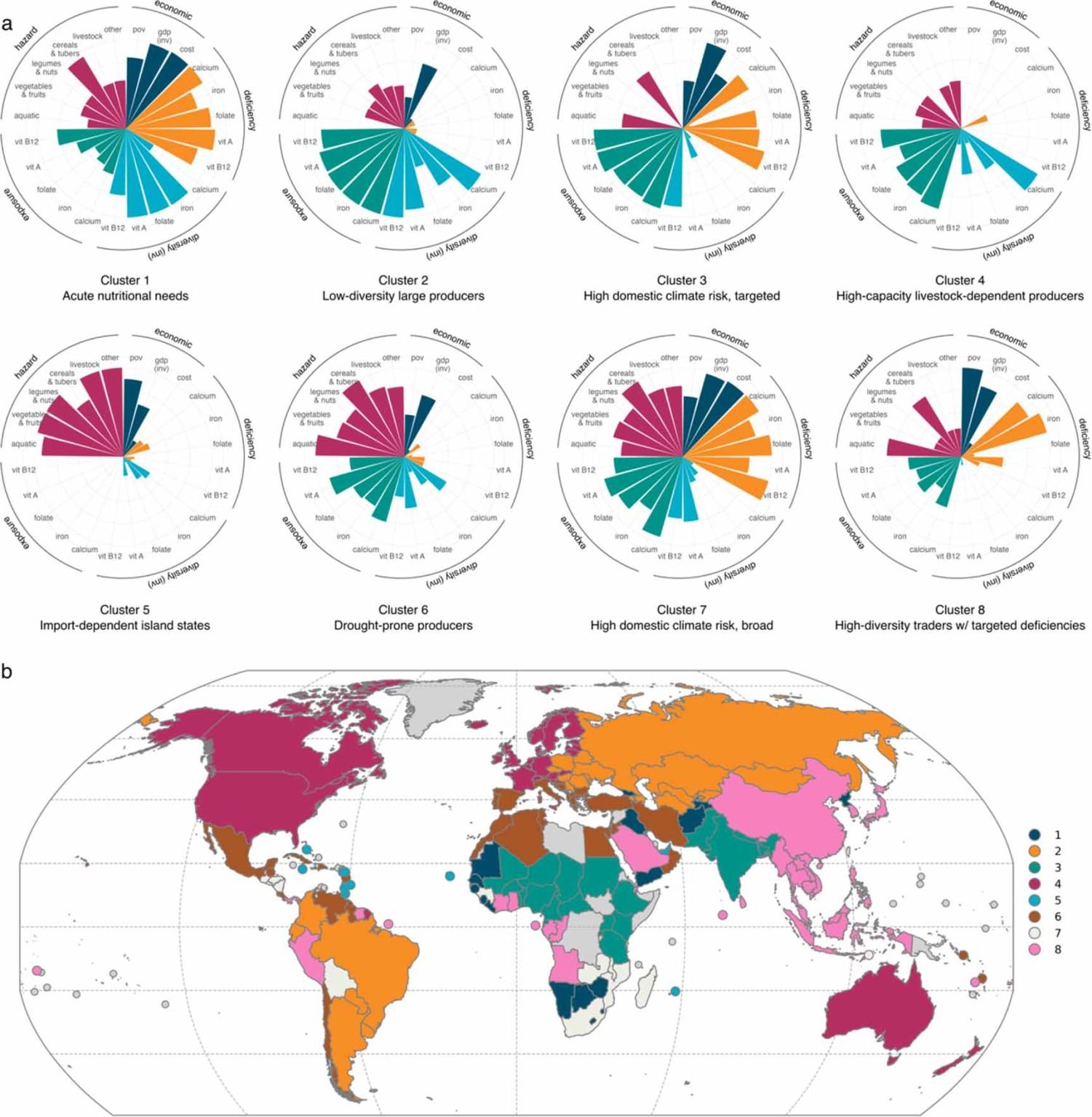

We used data from the Global Nutrient Database. We categorized food items into six groups: aquatic products, fruits and vegetables, legumes and nuts, cereals and tubers, livestock products, and other crops. We then analyzed the availability of these micronutrients. We linked this supply data to various climate hazards using an integrated approach that considers the impacts of climate change on food systems.

The major findings highlight significant regional variations in climate risks associated with nutrient availability, with notable hazards for vitamin B12 and calcium predominantly found in animal-source foods. By 2041–2060, most countries will face medium or high climate risk to at least one critical micronutrient (calcium, folate, iron, vitamin A, B12).

This figure hows how often each nutrient’s domestic production will face extreme climate 2041-2060. For example, vitamin B12 and calcium face high climate risk due to heavy reliance on animal-source foods. Globally, 75% of calcium, 30% of folate, 39% of iron, 68% of vitamin A, 79% of vitamin B12, and 54% of energy production is projected to face climate extremes by the middle of the century.

Moreover, the analysis reveals that regions such as the Mediterranean and Central America are particularly vulnerable to high climate risks across all studied micronutrients, underscoring the urgent need for tailored resilience strategies to combat rising malnutrition amid the ongoing climate crisis. Countries like India, Nigeria, Tanzania, Mozambique, Madagascar, and Guatemala are projected to face high domestic climate risk across multiple micronutrients. Diverse Production Systems at Risk: Not just cereals, but livestock, aquatic systems, fruits & vegetables, and legumes & nuts are all vulnerable—particularly in tropical and low-income regions.

Why is the research important?

It goes beyond staples: Most climate-food modeling studies focus on crops like wheat or rice. This one looks at nutrients that actually matter for health — like iron and vitamin A — and includes diverse food groups, including fish and vegetables.

It links climate change directly to human nutrition, not just yields or calories.

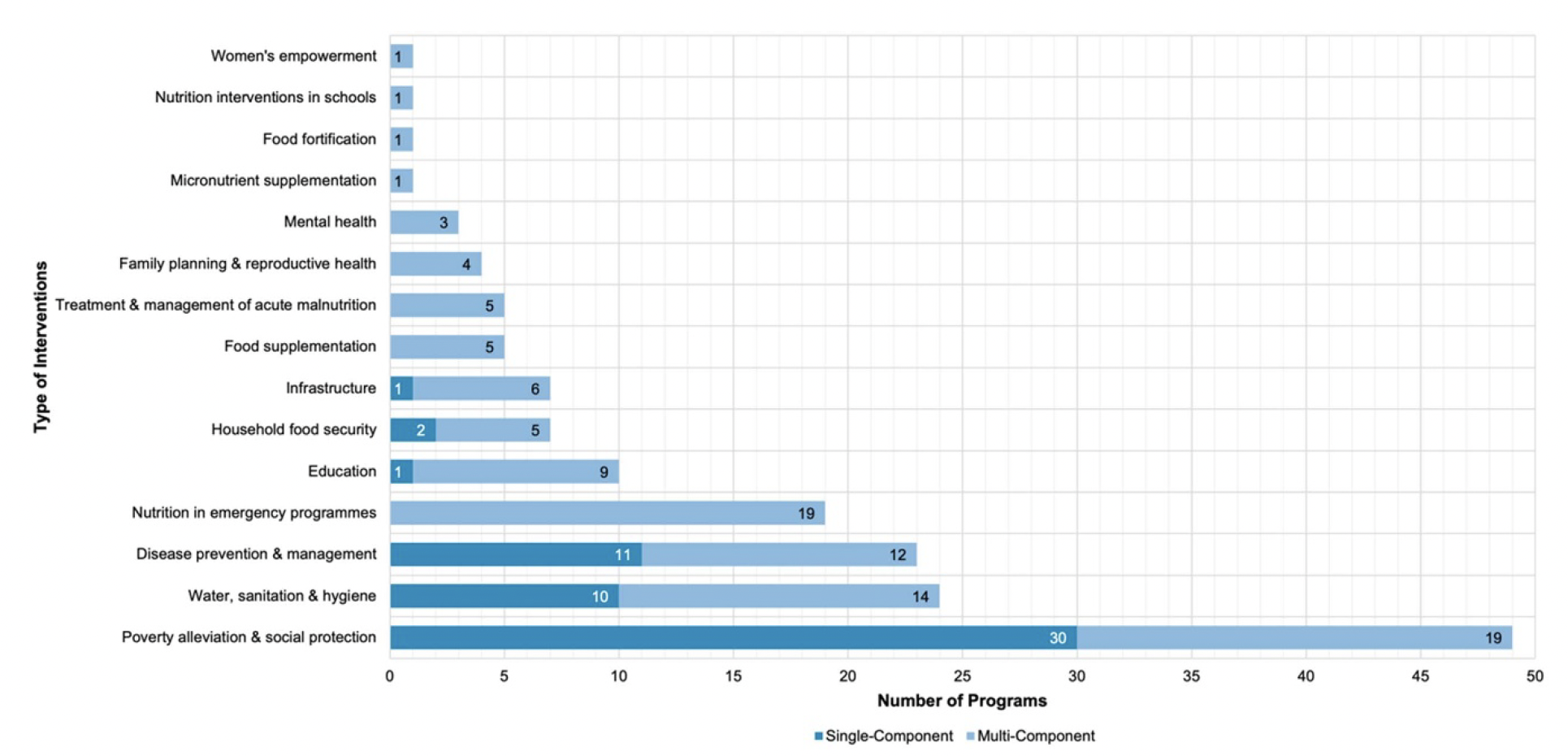

It recognizes that countries differ in their vulnerabilities and offers tools and strategies tailored to different kinds of risk profiles.

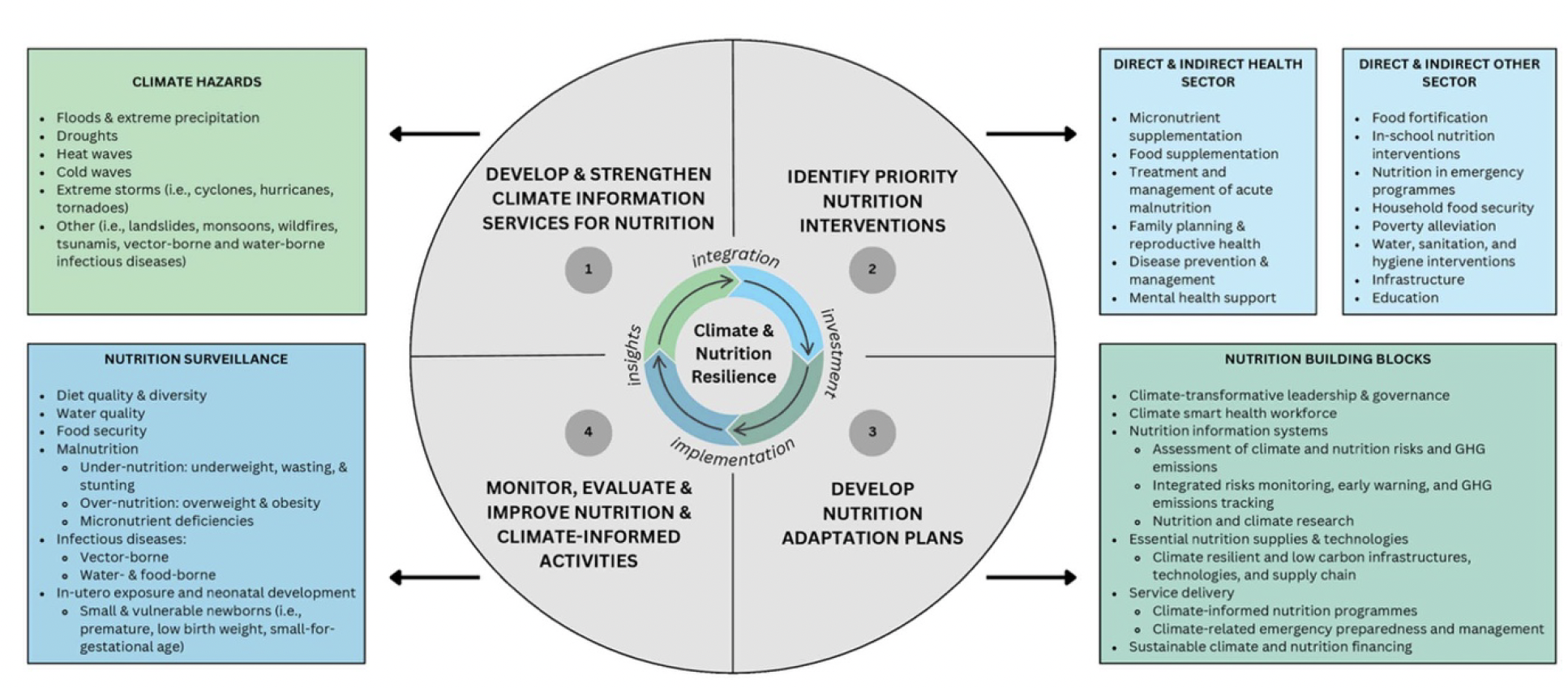

It provides a new framework for integrating food, nutrition, and climate policy. Countries can use this to prioritize where to invest — whether in farming, aquaculture, trade policy, or nutrition programs.

It shows that climate change threatens global nutrition goals, not just in fragile states. Even high-income countries could be affected if their food systems are too narrow or reliant on specific sectors.

What are the major calls for action?

Develop national commitments to nutrition in National FS Pathways, Nationally Determined Contributions and National Adaptation Plans.

Support diversified, climate-resilient food production.

Build food and nutrition security into market systems.

Expand safety nets and food environment policies to protect the most vulnerable.

I presented this work at the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition back in April 2025. Here is the slide deck. Enjoy!