As we wind down our time in Gotham and prepare to move abroad yet again, I’ve been reflecting on just how much New York has shaped my life. Since May 2000, my partner and I have lived here on and off, always orbiting back after stints in Nairobi, Rome, DC, and Bologna—four returns in total. In twenty-five years, we’ve logged about fifteen in New York, scattered across nine different neighborhoods. We are not people of permanence.

When someone asked if I’ll miss New York, my answer was immediate: I’ve already missed it for a long time. Not the city I live in today, but the New York that once was. The New York of the late 1990s and early 2000s, right before 9/11. Even in the aftermath of that day, with all its upheaval, I carried on a love affair with the city for another ten years. But eventually the itch came—the yearning to leave. Part of it was exhaustion. New York is relentless: chaotic, loud, dirty, and unforgiving. It wears you down. Another part was the way it shapes you into someone who sees the city as the only place that matters, the one true capital of the world.

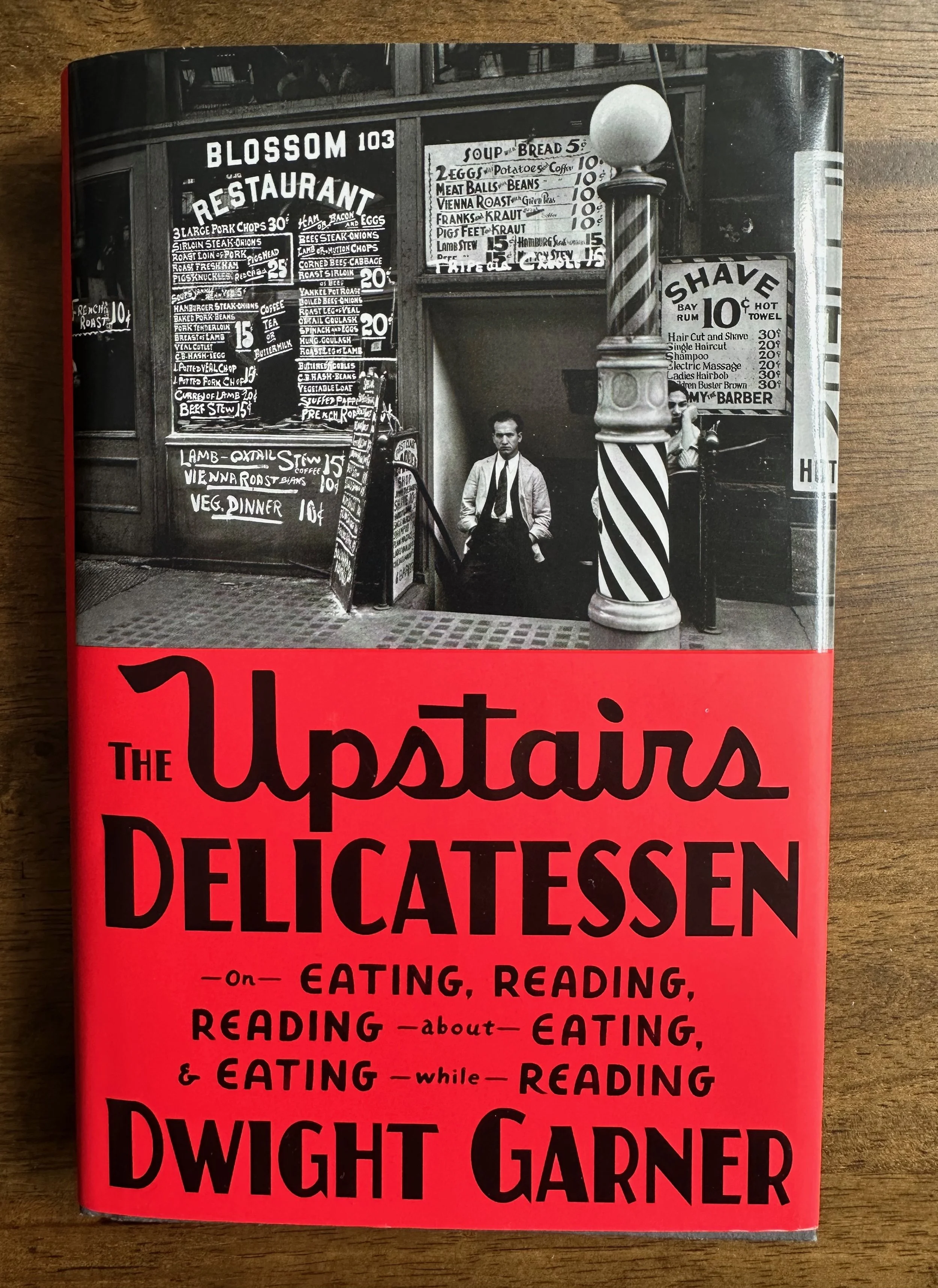

Those early 2000s—the “naughts”—in Gotham were formative for me. You could still afford to live here. Brooklyn was gritty and diverse, its edges not yet polished down. There was a music scene that felt electric, with bands like The Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and Interpol defining the soundtrack of the city. Hearing “Someday” by The Strokes pulls me straight into another era of New York—one that has, in large part, slipped away for good. You could eat well and cheap. You could stumble upon weirdness, originality, and true eccentricity across neighborhoods. That New York is gone, and I yearn for it daily.

The city didn’t change overnight. Gentrification and homogenization creep in slowly—minute by minute—until one day the skyline, the storefronts, even the people feel unrecognizable. Maybe it’s my age, but when I walk through the East Village or Williamsburg now, what once looked like a Saturday Night Live hipster parody has hardened into something even duller: tech bros and young influencers who talk, dress, and act in indistinguishable ways. Is everyone in this city from Ohio (apologies Devo, Chrissie Hynde and Eugene Lim!)? The former eccentricity of New Yorkers—the artists, the misfits, the characters—is gone. The mom-and-pop shops, diners, and dive bars have been swallowed by banks, chain stores, and pharmacies. Inventions like Dime Square and other fabricated micro-hoods, drenched in performative douchebaggery, have hollowed out the authentic, polyglot, diverse neighborhoods that once defined New York. Even the new green spaces look curated and glossy, like architectural renderings come to life. As LCD Soundsystem sang: “New York I love you, but you’re letting me down.”

Yes, New York has always struggled with decay and dysfunction—the litter, the scaffolding, the crumbling infrastructure. That’s not new. What’s changed are the people and the prices. Where the city once drew dreamers, hustlers, and artists, it now caters to a wealthy few who can pay $10,000 a month for rent or $200 for a couple of veggie burgers and beers in the Village (yes, these are indeed the real costs). The city feels hollowed out by inequity. Even walking—once the one free, joyful thing every New Yorker did—has become dangerous, with streets overtaken by e-bikes, delivery scooters, and battery-powered chaos.

This little video is a time capsule we made over 15 years ago at Pier 40 on the Hudson, back when the piers were abandoned. We liked it that way—wild, crumbling, full of possibility. Now it’s a manicured park, $100 million later, surrounded by the glass spires of Hudson Yards. In that old video, the soundtrack was The Chameleons’ “Less Than Human.” Looking back, the title feels prophetic.

And so, once again, it’s time to say goodbye. I doubt we’ll come back. Each return has carried the false hope of finding the New York we first knew twenty-five years ago, only to be confronted with its absence. As Arundhati Roy once recalled a friend telling her, “You’ve lived too long in New York… There are other worlds. Other kinds of dreams.”