Pastoralists—communities who raise livestock in arid and semi-arid lands—are central to food security in Kenya and much of Africa. They practice transhumance, moving herds seasonally between grazing areas to match forage availability, and employ extensive knowledge of variable landscapes to thrive where others struggle. Their mobility, social networks, and deep environmental understanding make them incredibly resilient. Pastoral communities supply large shares of milk and meat in regions where farming is nearly impossible.

Photo taken by Jess in northeastern Kenya, 2008

Pastoralism covers more than half of the Earth’s land surface, supporting hundreds of millions of people, especially across Africa and Asia, in areas where conventional farming doesn’t work. In Africa alone, the African Union estimates that pastoralism contributes between 10% and 44% of national GDP in pastoralist-reliant countries—underlining its economic significance and the structural risks of sidelining these communities.

But their way of life is under increasing threat. Worsening droughts, shrinking access to water and grazing land, and competition over scarce resources have made it harder to sustain herds. Many pastoralists, especially the younger generation, are leaving behind livestock herding for other livelihoods, but these alternatives are often limited, insecure, or inaccessible to the poorest. As one pastoralist put it starkly: “The future for pastoralists is dark unless something is done.”

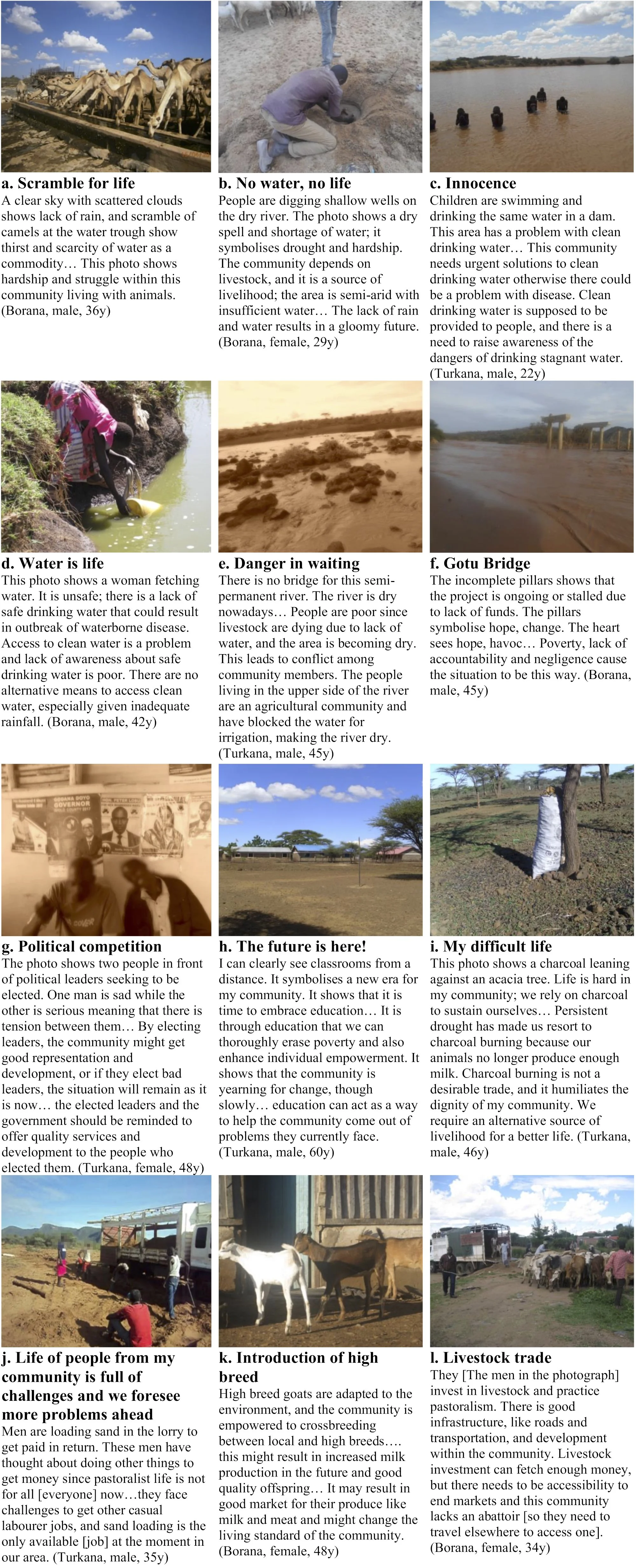

A new study published in Ecology and Society, led by Elizabeth Fox (now at Cornell), who at the time was a postdoc in my group, in collaboration with colleagues in Kenya, worked with Borana and Turkana communities in Isiolo County, Kenya, using photos and interviews to capture pastoralists’ own perspectives on what’s happening. People described how climate change has eroded traditional coping strategies, such as moving with herds or relying on community networks. Land once shared is now fenced off for farming, conservation, or settlement. Traditional authority structures have weakened, and political representation remains limited. Many participants felt neglected by leaders and frustrated by top-down programs that provide mismatched support—like giving seeds when there’s no water. Some have turned to short-term survival strategies such as charcoal burning, which are environmentally destructive and unsustainable.

Below shows the story of pastoralists – through their eyes – using photo elicitation in which pastoralists were given cameras, asked to take pictures about the “story of pastoralism” and then select the photographs that were most salient to them. They chose the titles and descriptions of each photograph.

Yet, pastoralists also identified opportunities for a more hopeful future (see table below). They pointed to the need for practical interventions: better veterinary care and water infrastructure, land rights and grazing corridors, fair livestock markets, training for value-added businesses, and education that creates diverse job opportunities without abandoning pastoral traditions. Most importantly, they emphasized being included in decisions about their future. The takeaway is clear: pastoralists already know what they need. The challenge is for governments and development partners to listen, invest in equity, and support solutions that allow pastoralist communities to thrive while adapting to climate change. Without this, not only pastoralists but also the broader food systems they sustain stand to lose.

This pastoral way of life is vulnerable unless safeguarded. Policies that restrict mobility, privatize grazing lands, or ignore pastoral voices threaten not only their survival—but the broader ecological balance they help maintain. Supporting pastoralists with secure grazing corridors, recognition of communal rights, and adaptive governance isn’t charity—it’s an act of stewardship for resilient, sustainable futures.

This research was just published in Ecology and Society (2025) and is available here.