Trigger warning: This blog has nothing to do about food! Ironically, last month I posted a blog about hued grief—reflecting on what has been lost in the past year in the U.S. What I didn’t mention is that I have been grappling with a personal grief of my own: the passing of my mom. As my Rector at the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) Europe wisely noted, “I know from experience that such events always find us somehow unprepared, even though they are in the order of things.” Well said. Losing a parent is an utterly heartbreaking experience. Interestingly, it’s a journey that most people undergo, so this feeling is not unique to me.

As one navigates these kinds of losses, it fosters profound reflection on where to go from here, especially when you no longer have that relentless cheerleader in your corner. What I’ve come to realize over the past year resonates deeply with me: embrace every sandwich, live life on your own terms, make bold moves (thank you, Ani DiFranco, for the inspiration), and find a way to kick around in the wreck. It’s essential to be okay with grief, to be okay with anger, and to give yourself permission to heal. LIVE YOUR LIFE ON YOUR TERMS. We all know this, yet it has taken me 54 years to fully grasp what it truly means.

One of my dearest friends and hermano, Mario Herrero, asked me the other day, “What are your plans?” It’s a perfectly reasonable question now that I’ve moved to a new country, city, and job. I had no answer for him; my response was simply, “I don’t know.” And he said, that’s okay.

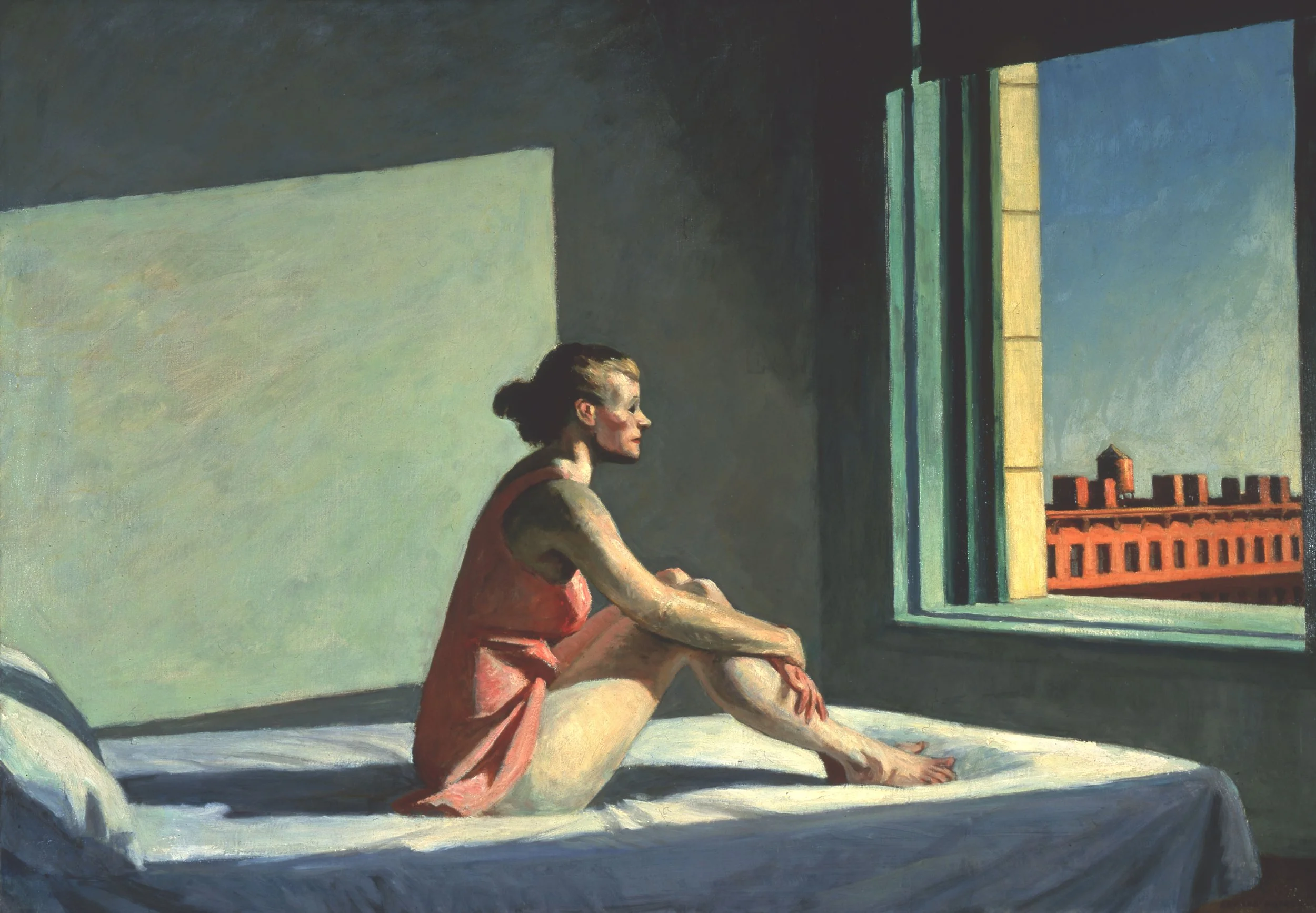

Last year, one of my goals was to practice the art of NIKSEN. This Dutch term literally means “to do nothing,” but it isn’t the same as boredom or laziness. Niksen invites you to break free from the daily grind of work, family demands, and social pressures. It’s about destressing and simply stopping. It involves intentionally doing nothing without purpose or deadline: gazing out the window, taking in the scenery, and allowing your mind to wander. As John Lennon sang, “I’m just sittin’ here watching the wheels go round and round.” Yup.

Edward Hopper. Morning Sun

I’m not saying I’m checking out of the world. Instead, I intend to engage more thoughtfully. I recently wrote about handing over batons to the next generation (more beef, less bear). I made my mom proud a long time ago, and one of her enduring wishes was simply for me to be happy, a sentiment I hope for all of you, my dear readers. Find joy in the everyday. It can be challenging as the world seems to be unraveling, but remember: there are only a handful of people who want to watch the world burn. The majority of humanity cares deeply about our world, our future, and our collective progress. We face many hurdles, but history teaches us that we can overcome them.

Philosopher Martha Nussbaum, in her book The Monarchy of Fear, argues that fear is a primal, narcissistic emotion currently dominating American political life. It fosters anger, envy, and disgust, all of which threaten democratic values. While fear may be the "first prescribed emotion," it is not our destiny. We have the power to dismantle the "monarchy of fear" by choosing to build a society rooted in shared humanity and justice. Moreover, if you observe the ebbs and flows of the world, you’ll see that it is indeed a better place. We experience setbacks, but progress is being made.

Relish in that thought and remember it. Find what matters to YOU and fight like hell to keep it close to your heart. Because ultimately, it all comes to an end for each of us, and what truly matters is that you lived your best life on YOUR terms—not the terms set out for you by others.