If you want to read a food book this year, read Eating to Extinction: The World's Rarest Foods and Why We Need to Save Them by BBC food journalist Dan Saladino. The book is about the rich biodiversity found around the planet and how humans have used that biodiversity to feed the world's population. Saladino illustrates how important this diversity is for our nourishment and sustaining the vast cultures and traditions that humans have passed on from one generation to the next. Not only is Saladino a wonderful storyteller, but the story he is telling is one of the most important in food systems today. He writes:

"We cannot afford to carry on growing crops and producing food in ways that are so violently in conflict with nature; we can't continue to beat the planet into submission, to control, dominate and all too often destroy ecosystems. It isn't working. How can anyone claim it is when so many humans are left either hungry or obese and when the Earth is suffering?"

Saladino structures the book across the main food groups — fruits, vegetables, grains, cheese, meat, seafood, alcohol, stimulants (coffee and tea), sweets, and wild foods. He discusses the importance of these food groups and their role in food security. He provides us with lush, visceral vignettes of particular places, exceptional people, and distinctive cultures uniquely trying to grow, raise, and nurture certain traditional varieties of these foods. You get a glimpse of how the hunter-gatherer Hadza hunts for honey in Tanzania. You learn how sheep meat, known as Skerpikjot, is preserved in the fragile ecosystem of the Faroe Islands. You feel the pressure of how Sicilians grow the vanilla orange amid the weight of the Cosa Nostra. You sympathize with the Syrians amid a protracted conflict who attempt to preserve their traditional sweet, Halawet el Jibn, made of war-threatened ingredients like pistachio. You realize that winemaking began in Georgia using traditional pots, known as Qvevri, a practice not done anywhere else in the world.

These stories are wonderful, but they are punctuated with startling and tragic statistics:

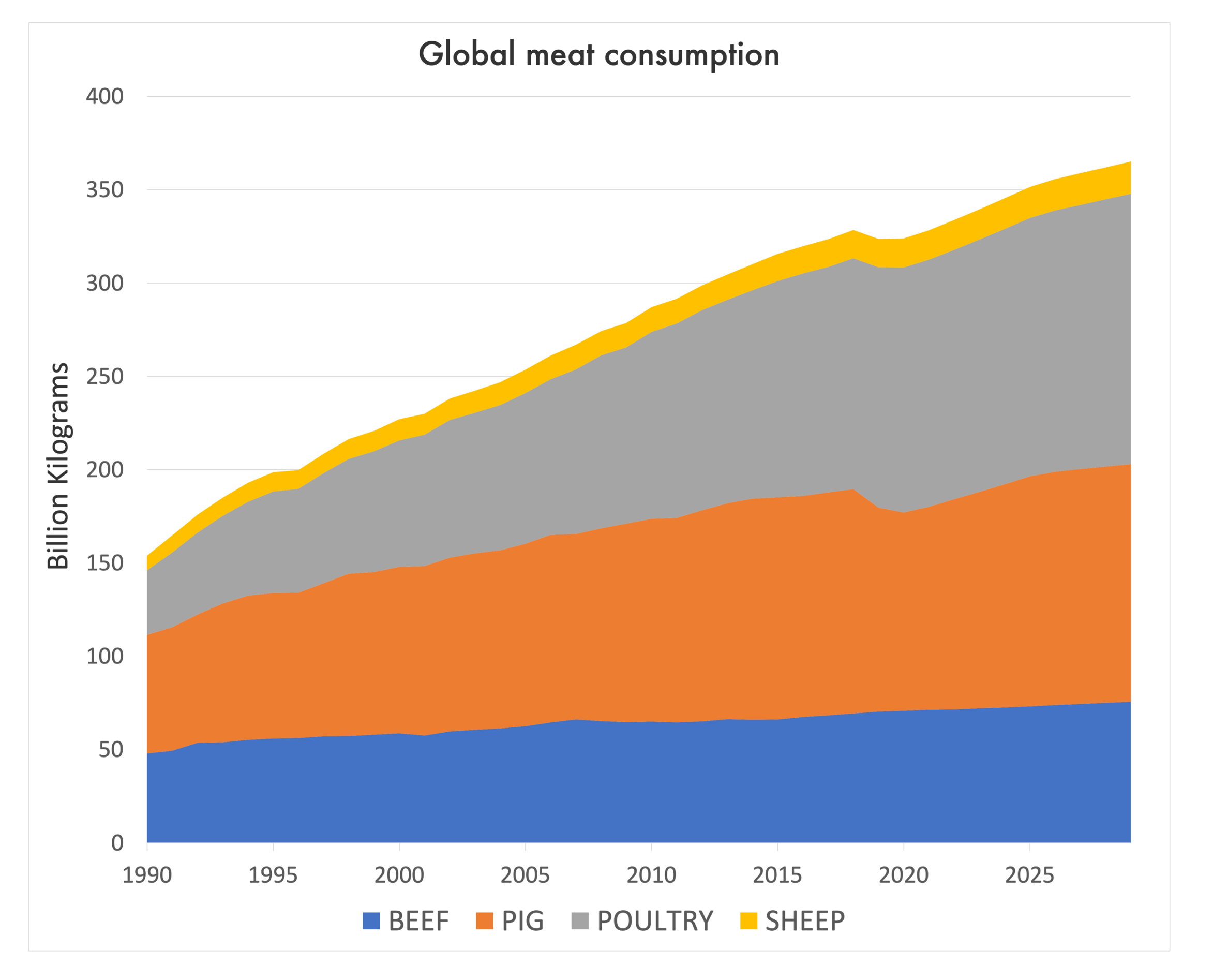

50% of all our seeds are in the hands of 4 companies.

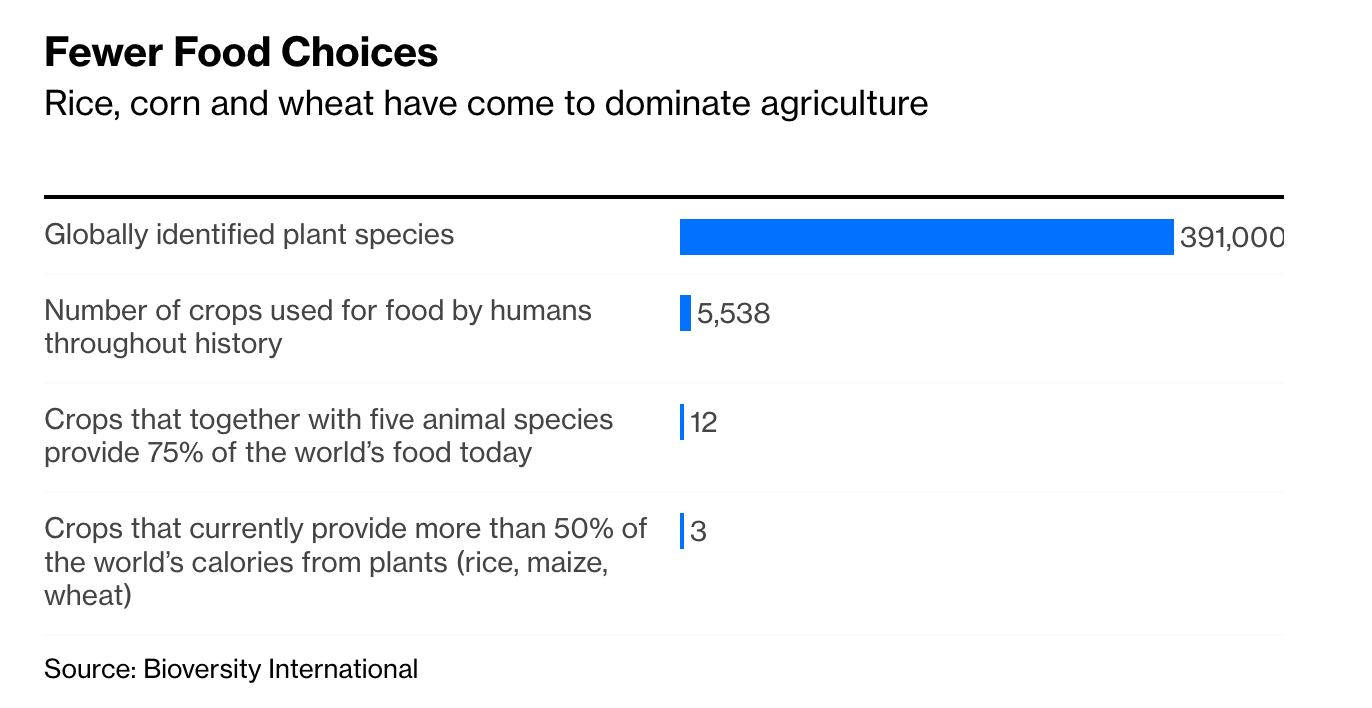

Of the roughly 6,000 different plants once consumed by humans, only nine remain major staples today.

Three crops—rice, wheat, and corn—provide 50% of all our calories.

70 billion chickens (of roughly the same breed and ironically named "chicken of tomorrow") are slaughtered annually.

30 million bison roamed the great plains of the United States, all to be decimated at the hands of the white settlers.

95% of milk consumed in the United States comes from a single breed of cow.

90% of soybean grown in North and South America is genetically modified.

50% of all the world's cheese is made with bacteria or enzymes made by one company

The giant Pacific bluefin tuna is down 97%. Yes, 97%.

Only 2% of farmers are African American.

We only consume 2% of barley that is grown. The rest is used to make beer or fed to animals.

Speaking of beer, 25% of beer is produced by one brewer.

You learn about the heroes, like Vavilov, who spent and gave their lives conserving and preserving precious seeds, specific varieties, preservations, and processing of foods as a way to say, "remember us." We were here. They were and are the custodians of the biodiversity across the planet. They are also the custodians of our memories and humanity.

As Saladino escorts you around the world, I imagined these vignettes being turned into a beautiful documentary demonstrating the vast diversity that exists on the planet—as humans, as foods, and as cultures. As Saladino expressed, we must embrace diversity in all its forms: biological, cultural, dietary, and economical. Having more diversity across the range of agriculture systems and landscapes is vital. Capturing all this diversity on film, as the book does, could be a way to preserve these moments, memories, and the history of it all. So, we never forget what we once had.

While the book is inspiring, every chapter ends with a common tragic theme – and I am not giving anything away because it is in the book's title: Extinction. You realize how fast these ways of life, these foods, these cultures, and traditions are disappearing. Our world and food systems are transforming at a speed that is hard to comprehend and capture, and the loss along the way is disturbing. There are many reasons for this extinction, but the major ones are agricultural change, loss of habitats, disease, economic forces, hangovers and continuations of colonization, and conflict.

As Saladino expressed, these endangered foods will not become the mainstay of diets, nor should they. But they have essential and assorted roles to play; if we don't use them, we will lose them. In reference to a chapter on O-Higu, a soybean grown on the island of Okinawa made into unique tofu, "O-Higu might be an insignificant bean. But to many Okinawans, after colonialism and occupation, its return feels like an act of resistance and a celebration of who we are." Many traditions in holding onto these foods are worthy; they involve intimate knowledge, special skills, and lots of care and labor. It is not a simple path forward.

Our world and food systems are transforming into a homogenized vat of staleness. For many, saving these foods and the biodiversity that makes up these foods and our diets is not worth the effort as we move through the world at warped speed. Some argue that this savior complex is romantic and precious, and we should instead focus on the potential for technology and innovation. Growth, growth, growth. Call me sentimental, but I worry about solely following this path and what is lost along the way.

Last night, I watched Chris Marker's visceral Sans Soleil film. In it, the narrator said something that sticks with me:

When filming this ceremony, I knew I was present at the end of something.

Magical cultures that disappear leave traces to those who succeed them.

This one will leave none; the break in history has been too violent.

I want to witness the traces. I want to remember. What is the point of living in this world without cultures and all the food that punctuates those cultures? We must, as global citizens, decide what kind of world we want to live in and figure out what is worth saving. To me, it is the whole lot. I want to save it all—every food, every human, every animal, and every piece of culture. This is what makes our world interesting. As Saladino said, "the Hadza remind us that there are many ways to live and be in the world." I am hanging onto my hopes that the incredible array of people curating these endangered foods will remain the custodians of not only our memories but of our food traditions for the future.